It took five days, but a power-sharing agreement was reached in the United States Senate. It’s necessary, since the Senate is split right down the middle: 50 Democrats, 50 Republicans. The tie can be broken by the vice president, who is also known as the “President of the Senate.” The item that held up agreement was the filibuster. Many Democrats want to kill it, since it’s a way for the minority to obstruct the majority. Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell agreed to allow the Senate to begin work, because two Democrats [Sens. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.)] agreed to vote against eliminating the filibuster.

Many of us only know the filibuster through Frank Capra’s 1939 movie, “Mr. Smith Goes to Washington.”

In it, Jimmy Stewart plays a good local man who is rather naïve. Party leaders decide to send him to the Senate, since they figure he wouldn’t be sophisticated enough to cause trouble. But Stewart catches on fast. He proposes that the government lend money to buy land for a boys’ camp, saying that kids would pay the government back, with nickels and dimes they’d send in. However, the land he wants is part of a pork-barrel dam building project. In order to hold up the dam project, Stewart “debates” the bill for 25 hours, until he collapses.

In the movie, people rally around him, and his senior senator (Claude Raines, who also played the chief of police in Casablanca), tells the Senators that Stewart was right all along, and the dam project should be scuttled. Heartwarming fiction.

That was then. The filibuster required someone to hold the floor. Today, we never have an actual filibuster. We just have threats of one, and the majority scampers away in fear. It takes 60 votes to shut off debate (“cloture”), and if the majority can’t find 60 votes, they just give up without trying.

The power of the filibuster has weakened a bit over the years. In 2013, Henry Reid used the “nuclear option” to kill the debate for administration confirmations and for votes on federal judges.

Then, Mitch McConnell expanded it to cover Supreme Court Justices. And, thus, this system of checks-and-balances was largely wiped out.

Most people think that a president should be allowed to appoint his own cabinet and federal officials, unless they have a conflict of interest, or are otherwise unfit. But the same can’t be said about the judiciary, where lifetime appointments make Justices invulnerable to accountability (short of impeachment). That’s why we have a Supreme Court that could be said to be composed of political hacks, who can be counted on to vote the same way every time, without consideration.

To create a more fair and balanced Court, appointments would require 60, 67, or even 75 votes. That would make it more likely that we would get Justices who are concerned with the will of all the people, as a whole, and not just the interests of their own, personal tribe. For the good of the nation, the filibuster for the judiciary should be strengthened, not eliminated.

Let’s look at what the filibuster is. The word “filibuster” comes from the Dutch word for “pirate,” and suggests the “maverick” nature of the activity. It goes back at least to ancient Rome.

One of the first known practitioners of the filibuster was the Roman senator Cato the Younger. Cato would obstruct a measure by speaking continuously until nightfall. As the Roman Senate had a rule requiring all business to conclude by dusk, Cato’s long-winded speeches could forestall a vote.

Cato used the filibuster so much that it finally caused a backlash.

A turning point came when a member of Cato’s faction angrily announced to the people’s assembly, “You shall not have this law this year, not even if you all want it!” — and had a bucket of manure dumped on his head for his troubles. With their opponents’ intransigence exposed so starkly, Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus were able to pass bill after bill by popular vote. . .

Is there a lesson here for today’s Senate? Cato’s endless obstruction succeeded wildly for a time, but it finally empowered his rivals and fatally weakened the Senate he cherished so much. It wasn’t any one filibuster that helped wreck the Senate’s legitimacy. It was a pattern of obstruction that had begun to look permanent.

And that is the point. People will put up with, and even admire people like Mr. Smith, but only to a point. The reason Senators should be forced to actually hold the floor is that the public will put up with only so much obstruction, and before long, the practice would only be used on the most serious issues, and if a Senator used it too much, he or she would incur the public’s ire.

In the U.S. it was often used by Southern Senators, to obstruct civil rights legislation, as early as 1850. The longest filibuster was conducted by South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond.

On August 28, 1957, United States Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina began a filibuster intended to stop the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957. It began at 8:54 p.m. and lasted until 9:12 p.m. the following day, for a total length of 24 hours and 18 minutes. This made the filibuster the longest single-person filibuster in U.S. Senate history, a record that still stands today.

Thurmond was so against the 1964 Civil Rights Act that he became a Republican in 1964, and the entire segregationist Jim Crow “Solid South” switched from Democratic to Republican. President Lyndon Johnson acknowledged that, according to Bill Moyers, who was in a position to know.

When President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law on July 2, 1964, he is said to have told an aide, “We (Democrats) have lost the South for a generation.”. . .

Two months later, a key Democratic foe of civil rights, South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, switched his party affiliation and began working to remake the Republican Party so that it could appeal to Southern white voters. Thurmond was an essential backer of the campaigns of Goldwater in 1964, Richard Nixon in 1968 and Ronald Reagan in 1980. His influence on Nixon, who developed a so-called “Southern strategy” to help realize Thurmond’s vision of a transformed political map, was immense. It extended deep into the decision-making process for the selections of a vice president and Supreme Court nominees.

“A generation” was a gross understatement. Southern whites are still primarily Republican, more than 50 years later, just as they had been solidly Democratic back to Lincoln’s time.

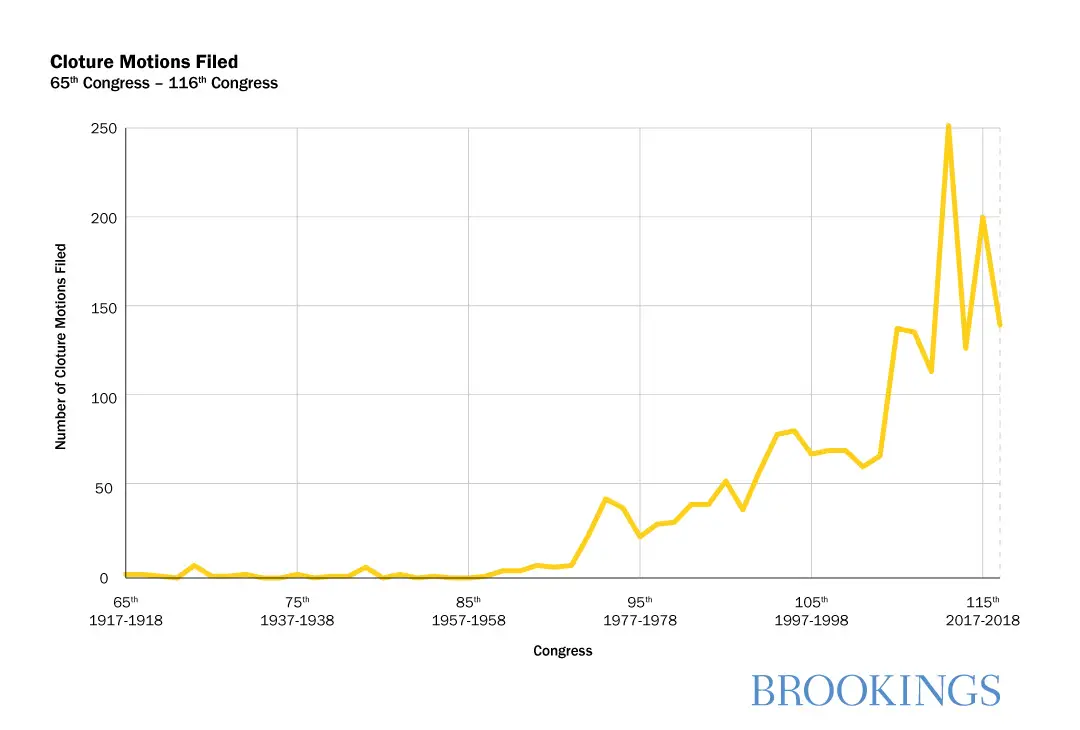

The filibuster reached a high point during President Obama’s second term—250 times in one year, or an average of once every working day.

Ending the filibuster is hard—because the move, itself, could be filibustered.

The most straightforward way to eliminate the filibuster would be to formally change the text of Senate Rule 22, the cloture rule that requires 60 votes to end debate on legislation. Here’s the catch: Ending debate on a resolution to change the Senate’s standing rules requires the support of two-thirds of the members present and voting. Absent a large, bipartisan Senate majority that favors curtailing the right to debate, a formal change in Rule 22 is extremely unlikely.

However, a more arcane method can be used.

A more complicated, but more likely, way to ban the filibuster would be to create a new Senate precedent. The chamber’s precedents exist alongside its formal rules to provide additional insight into how and when its rules have been applied in particular ways. Importantly, this approach to curtailing the filibuster—colloquially known as the “nuclear option” and more formally as “reform by ruling”—can, in certain circumstances, be employed with support from only a simple majority of senators.

The nuclear option leverages the fact that a new precedent can be created by a senator raising a point of order, or claiming that a Senate rule is being violated. If the presiding officer (typically a member of the Senate) agrees, that ruling establishes a new precedent. If the presiding officer disagrees, another senator can appeal the ruling of the chair. If a majority of the Senate votes to reverse the decision of the chair, then the opposite of the chair’s ruling becomes the new precedent.

If Democrats try this, they are likely to regret it. The Senate is set up to allow “empty” states to have equal power with largely populated states. For instance, California has a population of more than 39,500,000, while Wyoming has fewer than 579,000. That is, California represents more than 68 TIMES as many people, yet the two states have the same, exact Senate representation.

In today’s America, population centers vote Democratic, while rural areas vote Republican. Thus, it’s a lot easier for Republicans to gain control of the Senate. And therefore, Democrats should beware of what they wish for.

Donate Now to Support Election Central

- Help defend independent journalism

- Directly support this website and our efforts