Two interesting articles popped up the last few days. The Daily Beast says that Hillary Clinton is the Jeb Bush of the left. Meanwhile, the same publication says Hillary is this year’s Richard Nixon. Imagine how happy Hillary must be with the comparisons! But more importantly, will we want to elect Jeb Nixon?

How is Hillary like Jeb? Both were supposed to be “inevitable,” but there’s more.

Wonky. Earnest. Bathing in Benjamins. The Democratic frontrunner and the Republican belly-flopper are more similar than you think. . .

Like Jeb, she put in the time in the policy trenches. She earned it. And like Jeb, she literally spent decades meeting donors, building teams, growing trust with party officials, fostering loyalties—doing everything right. Jeb and Hillary headed into their parties’ respective primaries with godlike name ID’s and rapper money. And everyone freaked out; the parties, after all, would decide—so how could they not win?

. . . Oversold and overestimated, the pair demonstrate just how meager is the appetite for centrist-leaning, dynastic optimists. Jeb’s defeat foreshadowed Clinton’s struggles. So the facts are hard to get around: Hillary is the Jeb of the left. . .

Clinton’s eventual likely success will be due to her ability to be even Jebbier than Jeb—even more money, even more endorsements, even more intimate connections with even more power-brokering elites (they even share a few donors!). But power-brokering elites ain’t what they used to be. . .

Clinton and Bush share many of the same flaws: social awkwardness, boundless capacity for gaffeing, acute interest in issues that literally zero voters find interesting, and a singular ability to seem inauthentic even when they were just being themselves. . .

Maybe we should’ve seen this coming decades ago. When Bill Clinton became governor of Arkansas, many murmured that his wife would have been better suited for the gig. . .

In similar (or, well, identical) fashion, conservative thinkfluencers held that Jeb would have been far superior to George W. as president.

That article focused on Hillary’s weaknesses. But the next argues that some of those weaknesses may actually be strengths. He compares today to the violent year, 1968.

There was the quasi-socialist Gene McCarthy, and the harsh-spoken populist, George Wallace. There were violent protests on both sides, and the Dem nominee was seen as wishy-washy.

Drawing on material from his new book, American Maelstrom, Michael A. Cohen shows how Clinton is working from Richard Nixon’s comeback playbook.

[There was] the “Clean for Gene” insurgency led by Eugene McCarthy [Like Bernie]. . . There was the rise of George Wallace and the primal violence that accompanied his political rallies [Like Trump]. . . Yet, the one person often given short shrift when we talk about 1968 is the one who was the last man standing when all was said and done—Richard Nixon.In a year when grassroots political movements helped to topple Lyndon Johnson and got George Wallace on the ballot of all 50 states and 13 percent of the popular vote on Election Day, it’s perhaps the greatest irony of 1968 that a leader who was the embodiment of the political status quo ended up prevailing on Election Day.

. . . in much the same way that Richard Nixon won the presidency in 1968, by speaking on behalf of what he called, the non-shouters and the non-demonstrators, Hillary Clinton is following a very similar path. . .

It would be unfair to compare Hillary Clinton to a man who as president conducted a criminal conspiracy from the Oval Office, but the similarities between their pursuit of the White House are hard to ignore. Like Nixon, Clinton encountered political humiliation in losing the 2008 Democratic nomination, a race she had long been favored to win. Like Nixon, Clinton worked tirelessly to keep herself in the public eye after that defeat—taking on the job of Secretary of State for the man who bested her in 2008, Barack Obama.

Like Nixon, Clinton was still unable to appease the fears within her own party that she is too moderate, too calculating, and fundamentally unelectable. But also like Nixon, Clinton has demonstrated the kind of dogged determination, policy mastery, and political discipline to outlast her challengers. And like Nixon, her ace in the hole was the support of her party’s political base, the rank-and-file voters who are more inclined to reward loyalty, embrace pragmatism, and seek a safe harbor than they are to start a political revolution.

As the likely Democratic nominee, she will enter the general election. . .as the symbolic adult in the race, a candidate of competence, clear qualifications, and experience who can run a campaign predicated on the theme of uniting Americans at a time of disunity—just like Richard Nixon in 1968.

Could this possibly be the case? Will voters be ready for “boring,” after a year of chaos and demeaning campaigning? Maybe so. After the macho presidency of George Bush, the public seemed to like the “professorish” Barack Obama. But we, as a people, grew tired of his mild manner and second-guessing, and his ratings dove.

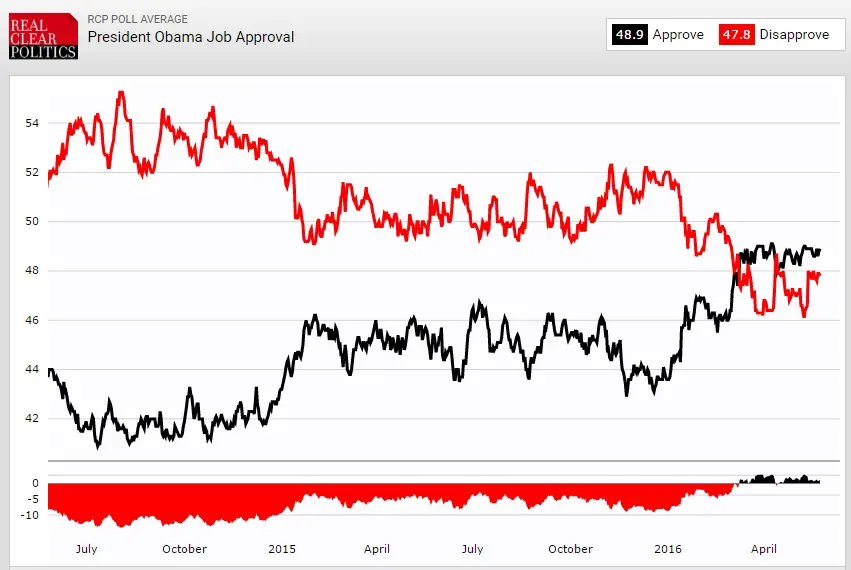

But now, after all the chaos and name calling in the GOP debates, and the protests on the Dem side, the public seems to already miss “No-Drama Obama.” Look at this chart from Real Clear Politics.

When the campaign started last August, only 41.6% of Americans approved of Obama’s job performance—and 55.3% disapproved. Today, more people approve of Obama than disapprove. Now, 48.8% think he’s doing a good job, while 47.9% don’t. He just doesn’t look that bad, compared to those who might succeed him.

And after a very long, annoying, sometimes disgusting campaign, maybe voters in November will be in the mood to be bored.

Donate Now to Support Election Central

- Help defend independent journalism

- Directly support this website and our efforts