We try to bring you what’s being said around the country in politics. Sometimes, it’s to point out the “common wisdom.” But we also like to give you what we find that is “not on the beaten path.” We had an article pointing out the irony that the Democrats poured millions into the special election race in Georgia, but ignored South Carolina, where their candidate did even better. But there’s a question of what money does for (or against) a campaign.

The “common wisdom” is that campaigns now need millions of dollars to be competitive. Since the Supreme Court oddly decided that money was the same thing as “speech,” we have a situation in which some people have more of a right to speech than others. But what does money do?

The Cook Political Report is a respected reporter and analyst of campaigns and trends. In a report Wednesday, Cook looked into the effect of big money, and came up with some interesting conclusions, comparing the Georgia and South Carolina races.

It’s a devastating psychological blow for a party to spend over $30 million on a House special election and still lose. For Democrats, Jon Ossoff’s defeat to Karen Handel stings, and the blame game is already raging: “Why did Ossoff run such a bland campaign? Why didn’t he take a sledgehammer to Trump and the AHCA? Don’t Democrats need to recruit little league coaches with deeper ties to their communities?”

This kind of second-guessing is a bit misguided. Last night’s results were far from a disaster for Democrats, and Republicans shouldn’t be tempted to believe their House majority is safe. In fact, their majority is still very much at risk.

First and foremost, just one state over, unheralded Democratic tax expert Archie Parnell – who ran on a similarly conciliatory, post-partisan message but generated a tiny fraction of the hype Ossoff did—shockingly came within three points of Republican Ralph Norman in a district President Trump carried by 18 points last November (Ossoff came within four points in a district Trump carried by one).

The thinking among many is, “if only we’d supported Parnell, instead.” But was it all about money?

Parnell’s near-miss has prompted outrage from activists on the left who believe he got short shrift from the DNC, DCCC and party hierarchy. If only the DCCC had parachuted into Sumter instead of Atlanta, the thinking goes, Democrats might have actually gained a House seat by now. But the reality is Parnell—much like Democrat James Thompson in KS-04—outperformed polls and expectations precisely because the race flew under the radar, not despite it.

The divergent results in GA-06 and SC-05 prove saturation-level campaigns can backfire on the party with a baseline enthusiasm advantage—in this case, Democrats. The GA-06 election drew over 259,000 voters—an all-time turnout record for a stand-alone special election and an amazing 49,000 more than participated in the 2014 midterm in GA-06. The crush of attention motivated GOP voters who might have otherwise stayed home, helping Handel to victory.

In other words, big money can be a negative, especially since big money draws big money. That is, while Republicans complained about the outside money going to Ossoff in Georgia, they don’t want to talk about a nearly equal amount of big outside money that went to Handel. And the expenditures cancelled out each other, annoyed the public, and may have been counterproductive.

In a low-profile race, it’s the motivated who bother to vote.

SC-05 drew fewer than 88,000 voters despite its similar population. Norman, the Republican nominee, had just emerged from a tight runoff with critical backing from the Club for Growth, but had alienated some of the district’s chamber of commerce types. Meanwhile, Parnell benefited from a base of highly motivated Democrats, including a modest and low-profile DCCC effort to turn out African-American voters.

Also, what good are special elections? The media are looking for hints about what will happen next year, but Cook says that’s backward thinking.

Second, overhyped special elections can often be lagging—rather than leading—indicators. In June 2006, Republicans retained a San Diego seat in a very expensive special election five months before losing the House. In May 2010, Democrats held an ancestrally Democratic seat in southwestern Pennsylvania six months before losing their majority. For a moment, tradition held. Today, both those seats are represented by the opposite party.

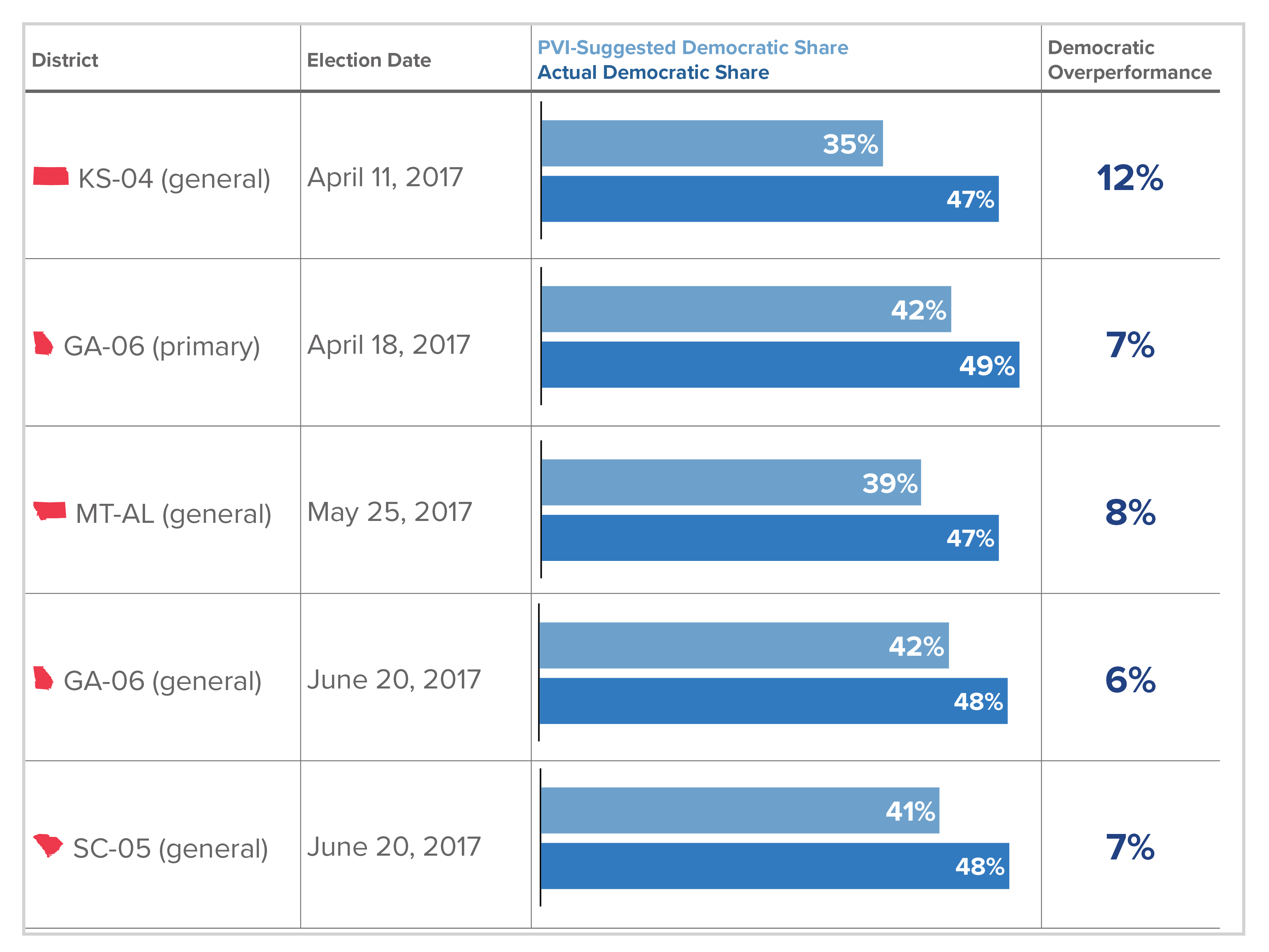

And for all the GOP chest beating and fist bumping, in ALL the special elections this year, it has been the Dems who have outperformed expectations. “Measured against the Cook Political Report’s Partisan Voter Index (PVI), Democrats have outperformed the partisan lean of their districts by an average of eight points in the past five elections:”

The article ends with this:

If Democrats were to outperform their “generic” share by eight points across the board in November 2018, they would pick up 80 seats. Of course, that won’t happen because Republican incumbents will be tougher to dislodge than special election nominees. But these results fit a pattern that should still worry GOP incumbents everywhere, regardless of Trump’s national approval rating and the outcome of the healthcare debate in Congress.

Put another way, Democratic candidates in these elections have won an average of 68 percent of the votes Hillary Clinton won in their districts, while Republican candidates have won an average of 54 percent of Trump’s votes. That’s an enthusiasm gap that big enough to gravely imperil the Republican majority next November—even if it didn’t show up in “the special election to end all special elections.”

The article posits that big money can be a negative, because it can bring out opposing voters, who think the big money will defeat their candidate. But considering that the parties performed almost equally in Georgia as in South Carolina, couldn’t we also say that the only thing big money did was (excuse the expression) piss off the people?

Despite the “Citizens United” mentality that says money is speech, and therefore, the rich and powerful have more of a right to free speech than the rest of us, maybe it’s time to put real limits on the spending that so annoys us and makes us cynical about our representatives. And while we’re at it, how about limiting the TIME allowed for a campaign, as they do in Britain? Do we really need two or more years of being beat over the head to decide which candidate we like? Does it really make sense to have our representatives spend more than half their time begging for money, instead of representing the rest of us?

It’s high time we asked those questions—and discussed them honestly and intelligently.

Donate Now to Support Election Central

- Help defend independent journalism

- Directly support this website and our efforts