The French returned Emmanuel Macron to his position of president. That was no small feat, as it’s the first time a president has been elected to a second term in two decades. But all the news leading up to the election focused on the strength of the far-right Marine Le Pen. The narrative was that France had made a right turn in politics, but that’s not what the numbers show.

While it’s true that in the first round, Le Pen increased her vote by two percent, Macron increased his vote by almost four percent. And, of course, the final vote of 58% to 41% is well more than what is considered a “landslide.”

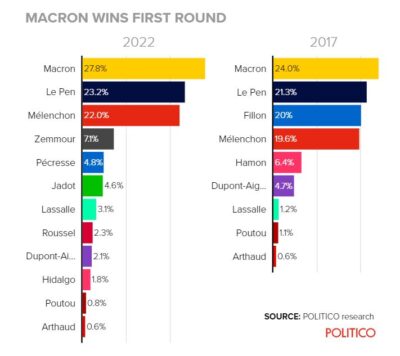

The first round vote in 2017 had Macron at 24% with Le Pen at 21.3% (a win of 2.7%). But in 2022, Macron upped his vote to 27.8% to Le Pen’s 23.2% (a win of 4.6%).

Even more telling is that there were four strong candidates in the first round in 2017, with the centrist Macron at 24%, the far-right Le Pen at 21.3%, rightwing Fillon at 20%, and leftist Melechon at 19.8%. If you add it up, the rightwing vote was 41.3%, with the centrist vote at 24%, and the leftwing vote at less than 20%.

The real story for 2022 was a turn to the left. There were only three strong candidates: centrist Macron at 27.8%, rightist Le Pen at 23.2%, and leftist Melechon at 22%. Only a little over 1% of the vote kept the leftwing candidate from going to the second round, instead of Le Pen.

In 2017, François Fillon actually looked like he could become the right-wing’s savior, and become president, but then he ran into a scandal when it was found that his wife had been paid for work she may or may not have done when Fillon was in government.

For a brief period – between November 2016 and January 2017 – François Fillon was the great hope of a resurrected French centre-right.

At 62, the former prime minister – long written off as an unexciting political dogsbody – had trounced the opposition in the Republicans’ party primaries and was seen as a shoo-in for next head of state.

In addition to breaking the precedent of one-term presidents, Macron also had to deal with another problem—himself. Suave and sophisticated, Macron was seen as aloof, and even arrogant.

In line with his high-and-mighty posture since the 2017 election, he has doubled down on Jupiterian aloofness. Macron refused to declare his candidacy until the very last moment. Condescendingly, he shunned invitations to debate with other candidates, and claimed affairs of state were more important than election campaigning. Why bother, when polls continued to give Macron a substantial lead over his rivals? This complacency may cost him dear. In the last few days, Macron’s lead has shrunk to within the margin of error of a lost presidency.

Recognizing this, Macron has developed an air of humility, which is likely to last for the full five-year term.

The re-elected president acknowledged this with uncharacteristic humility in his victory speech on Sunday. “Many of our compatriots voted for me not out of support for my ideas but to block those of the far right,” he told supporters at the foot of the Eiffel Tower. “I want to thank them and I know that I have a duty towards them in the years to come.”

The real surprise in the election was the strength of the left-wing candidate, especially among young voters.

Mélenchon didn’t prevent the expected duel between Emmanuel Macron and Le Pen. Yet there was some cause for satisfaction. His 7,714,000 votes was an increase of 700,000 on 2017 — even though last time he had three contenders on the Left and this time there were five. This was also the highest score for any radical-left candidate in the history of the Fifth Republic, founded in 1958.

As in 2017, Mélenchon came first place among young people. He was backed by one-third of eighteen- to thirty-four-year-olds, but only 9 percent of voters over seventy. It was voters over sixty-five who put Macron into the second round — a candidate who wants to raise the retirement age for everyone under sixty-five.

Often, there is a tendency to avoid “changing horses in midstream” when there’s a war. That is, stick with experience. But that was not a major concern. Le Pen showed strength, even though she is chummy with Russia’s Vladimir Putin, and has even advocated pulling France out of the European Union.

However, Le Pen also benefited because there was an even further right candidate in the first round.

The National Rally leader noticeably softened her speech in the run-up to the election, steering clear of controversy and putting a lid on the vituperations that once defined her party. Without renouncing her anti-immigrant stance, she studiously avoided talk of the “great replacement” conspiracy theory championed by extreme-right rival Eric Zemmour, which even the struggling conservative candidate, Valérie Pécresse, clumsily referenced. She knew, no doubt, that their hardline supporters would rally behind her in the run-off.

When Zemmour surged in the polls in late 2021, critics suggested Le Pen had gone too far in her efforts to “normalise” the former National Front – turning it from radical to bland. But party officials welcomed the shift in perception, noting that some analysts had stopped labelling the National Rally “far right”, adopting alternative labels such as “national populists”.

So, Le Pen appeared less extreme, thanks to Zemmour, who received only 7.1% of the first round vote this year.

Like America, France seems to be divided into dedicated liberal and conservative wings. Macron won again for the center, but by half as resoundingly as in 2017. And more importantly, the right and left now appear to have equal strength, so if the center falls, it’s anyone’s guess which way France might go in 2027, with the kind of whiplash we experience here. A relatively few votes can throw the country in an entirely different direction. And that’s not good for anybody.

Donate Now to Support Election Central

- Help defend independent journalism

- Directly support this website and our efforts